With ABA for 6 years, Catherine Jacobsen is a project manager working on projects from healthcare facilities to academic spaces.

During a recent session at Greenbuild, someone mentioned how designers are often the “handmaidens” of capital, which raised an interesting question: while we have the opportunity to vote with our wallets in our day-to-day lives, what power do we have as designers to create equity?

Looking back on my career to date and the projects that meant the most to me, this question has long had an influence on me. And from the common element to the various types of projects I’ve worked on over the years, the answer that comes to mind starts with the intention to provide spaces for those most in need.

One memorable project I’ve worked on was a teen center at Starbird Park identified in a plan developed for the Blackford community and funded by the then-redevelopment agency of San Jose under the Strong Neighborhood Initiative. Operated by the San Jose Parks, Recreation and Neighborhood Services Department with the aim of enhancing neighborhood conditions, strengthening community safety, and expanding services, the teen center included a classroom, computer lab, lounge, game room, and café. With LEED in mind, it was designed to take advantage of temperate climate to reduce energy use with a radiant heating system and a mechanical system that took advantage of cool nighttime temperatures to flush the building each evening and thermal mass to maintain a lower temperature within the building throughout that day. After opening to an enthusiastic public, it was incredibly rewarding for me to see how this safe and productive space was having a positive impact on the local community.

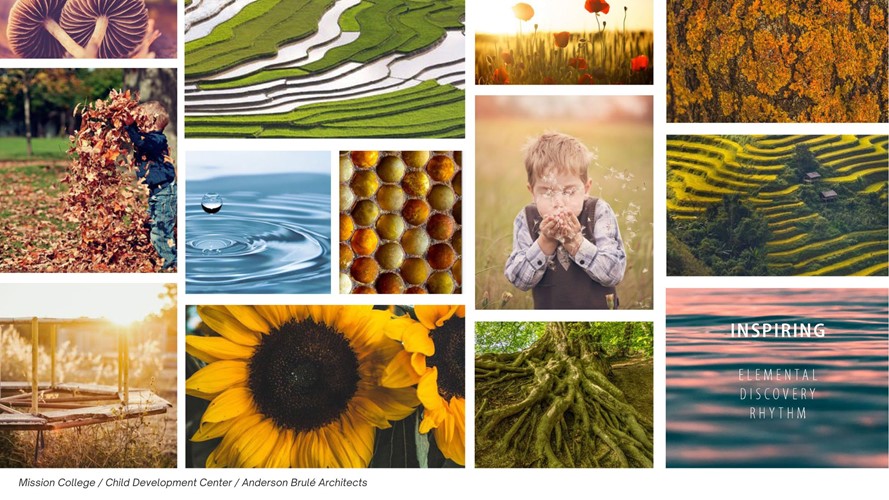

Another memorable project for me was for a new childcare facility developed as a part of a larger campus construction initiative at a continuation high school in San José, an effort intended to increase equity across San Jose Unified School District. The new facility serves the school’s Cal-SAFE Young Families Program, which encompasses childcare services for infants/toddles whose parents attend the high school as well as a child development program to teach students the skills needed to safely raise healthy and happy children. Designed to LEED Gold standards to provide a safe, comfortable and environmentally-conscious outcome, the building implements several important strategies, such as: 1) Orientation and design to maximize natural light and minimize energy use; 2) Rooftop photovoltaics to produce all of the energy needs of the building, and 3) Use of pervious materials and reflective coatings to mitigate heat island effects. Altogether, these strategies resulted not only in meeting the LEED Gold standards but in achieving the first Zero Net Energy Building for the school district. Most importantly, they form the backbone of an overall design that supports the functionality of the programs with physical conditions that equitably support overall comfort, health and wellbeing.

Most recently, I completed an engineering lab for a local high school, transforming an existing open space that served as a woodshop into a multi-media makerspace and flexible learning environment. In addition to creating zones for ideation, contemplation, and production, our team included a refuge space for students that learn and perform better in quieter environments. While a simple design element, its impact is highly meaningful to students with differences in how they best engage with their studies in the classroom. Similarly, the remodel of a small facility for the County of Santa Clara was modest in scope, but the update will have a tremendous impact, both in terms of individuals and the broader community, on a program to care for victims of sexual assault.

The Key to Good Design

Whether applying sustainable design principles on community projects or considering how even small design interventions can yield meaningful impacts, a project’s equitable outcome necessarily emerges from considering the experience of a place from multiple points of view. So when I’m asked about what characterizes good design, and how we can better balance the scales for those whose needs greatly outweigh what they currently have, my answer always starts with empathy. When I entered college still unsure of my path ahead, an assessment identified social work as a natural fit given my sensitivity to other people’s needs and viewpoints. But it was architecture that ultimately called to me, as an opportunity to actively shape the environments we all live in, bearing in mind that no project exists in isolation but rather is part of a larger community. It’s in the balance between the project and its context that empathy works well, as it not only leads to better design decisions but helps all user groups contribute to safe, enjoyable, just, and resilient built environments.